Main Image Credit: YourStory

We're inching toward a future in which robots will move through our buildings as comfortably as we do. They'll unload trucks in warehouses, deliver packages across cities, and maintain the mechanical systems inside our homes. Homeowners will walk through their door and see a "living manual" on their phone, a constantly updating map of every system in the house: water filters, valves, sensors, batteries, fixtures. When appliances break, the manual will already know the replacement part, the vendor, and the last technician who touched it.

Even months ago, this future would have felt like science fiction—but that's no longer true.

It's the logical, inevitable outcome of the transformation in the spaces we build, how we've built them, and who they're for. The implications of this shift touch everything from city planning to everyday life. The shift represents a marked turn in our perspective of space. Where we once designed space almost exclusively for humans, now we are designing it to share with intelligent machines that can move through space almost as easily as we do.

The biggest result of this shift, however, is an opportunity for space makers—architects, engineers, construction professionals—to build an economy in which the rewards of these changes are far more evenly distributed, and not just in the hands of the super-sized software companies.

To show you what I mean, let's go back a couple of decades.

(Your) Data Becomes Capital

During the early 2000s, Meta (then Facebook) was the perfect example of a company that built its fortune mining users' information and selling it for a high price.

Most users didn't really understand the value of their photos and personal information. And, while it may be hard to believe now, most people seemed shocked that any company would even want them. It took a crisis to realize that while users technically owned their information, en masse, Meta could generate far more valuable data. That data helped advertising companies understand buying behavior across huge swaths of the population, helped political parties sway elections, and made Meta a multi-billion dollar company before selling a single physical product.

It also formed the basis of the new economy of the 21st century.

Meta's example demonstrates three points:

En masse, data is worth money.

To the right audience, almost any large data set is extraordinarily valuable.

The owner(s) of these data sets are extremely well positioned to make money from their sale (or licensure)

Buildings Equal Data

I was working as an architectural designer in the early 2010s when I first heard the phrase "Buildings = Data".

This idea originated with the team at technology consultancy CASE (later absorbed into WeWork) and it inspired a generation of my peers to engage with the technology aspect of design, long before the current wave of AI enthusiasm.

The concept was simple: A building is more than bricks and mortar, it's a collection of decisions made physical. Every dimension, material, and adjacency encodes how humans solved a spatial problem at a particular time and place. Each of those decisions involved a network of humans representing different economic activities. And, with the advent of Revit, a new generation embraced the Building Information Model (BIM) - a literal database of these decisions modeled in space.

With this, each building became a record of human expertise that could be mined for insight.

Multiply those insights across hundreds or even thousands of projects and you get something larger than any single model: a collective memory of how space works. In this context, buildings are just another dataset that a business can use to extract value and grow revenue, much like user behavior data or linguistic data.

Credit: WeWork/Jason Schmidt

However, even with that giant leap in economic activity, the deeper potential of this idea wasn't immediately obvious outside of the small realm of architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC).

Building Data Equals Capital

Each generation of companies learns from the last.

Fast-forwarding to today, AI companies like NVIDIA, OpenAI, & Anthropic learned from its previous generation how to extract capital from the large digital datasets of words that was our social-media laden internet landscape.

They've harnessed that data to create Large Language Models (LLMs), putting them to work in chat interfaces like ChatGPT and Claude. The emergence of these tools have dramatically changed how I, and most every other software engineer I know, works. They've also not been shy – at least OpenAI hasn't been – about skating past the exchange of money typically required for the data they use.

Even now, another set of companies is already learning from this generation how to extract capital from a different type of data. Companies like FigureAI and World Labs are using spatial data to build Visual Language Models (VLMs) and World Language Models (WLMs).

Credit: Figure AI

These models have the potential to help machines understand the physical world we live in. The goal for these companies is to build a reach as wide as ChatGPT's, but with consumer-grade humanoid robots that do chores or maintain equipment or even build new machines.

However, one problem remains: The dataset of the physical world is neither as large nor as well constructed as the language data of the internet. World Labs' Founder, Fei Fei Li, paints a sobering picture of why that matters:

If you look at today's robotics learning efforts…we're so far from solving robotics that we really need to be sober about solving the data problem.

[...] Self-driving cars had to go through this for decades, solving the data problem.

And that's an even easier problem than robotics, because self-driving cars are a simpler form of movement compared to robots that manipulate everything and anything in the world. Having the simulation environment, simulation data, synthetic data is a key to success.

As Li says, the consumer-grade robot will require tooling to enable it and an enormous amount of data is required to build that tooling. Synthetic data seeks to make up that gap by creating new data that machines can learn from at will and while it can provide a kind of training wheels for neural networks, real physical data is like gold to a system that seeks to understand the world at large.

Antonello Romano suggests as much in their article Synthetic geospatial data & fake geography:

…synthetic data, which approximates real-world data, may not include all outliers present in the original dataset, even though these outliers are critical for certain contexts and applications. So is it a question of geographical scale or privacy concerns? Not only that. The quality of synthetic data heavily relies on both the original data and the generation model. It can inherit biases from the original data, and efforts to adjust datasets to eliminate these biases may lead to inaccuracies.

Synthetic data while a reasonable route to enabling this next layer is only one way forward - physical data is another.

Data of the Physical World

Over the past two years I've worked with Integrated Projects scaling of our Scan-to-BIM service and, more recently, leading the automation of our Scan-to-BIM product.

Our team has spent years manually turning laser scans into BIMs for architects, engineers, construction companies, and building operators. In that time I have seen how these BIMs have changed in the eyes of our clients. At first, they were raw material an architect could use to start their design, now they are the foundational layer a user can utilize to gain insight into their spaces. Our BIMs are what BIMs always promised to be: highly accurate, labeled spatial data that reflects the physical world as it exists in a specific point in time. We're creating the ground-truth infrastructure for the physical world.

Our workflow begins with mobilizing scan technicians on site to capture a building with LiDAR cameras, which produce point clouds: millions of digital points representing reality in 3D space. It ends with an organized, object-based model anyone can use to understand what is before they decide on what should be. We used to build those models manually, room by room. Today, our automation pipeline converts a point cloud into an editable floor plan in less than an hour.

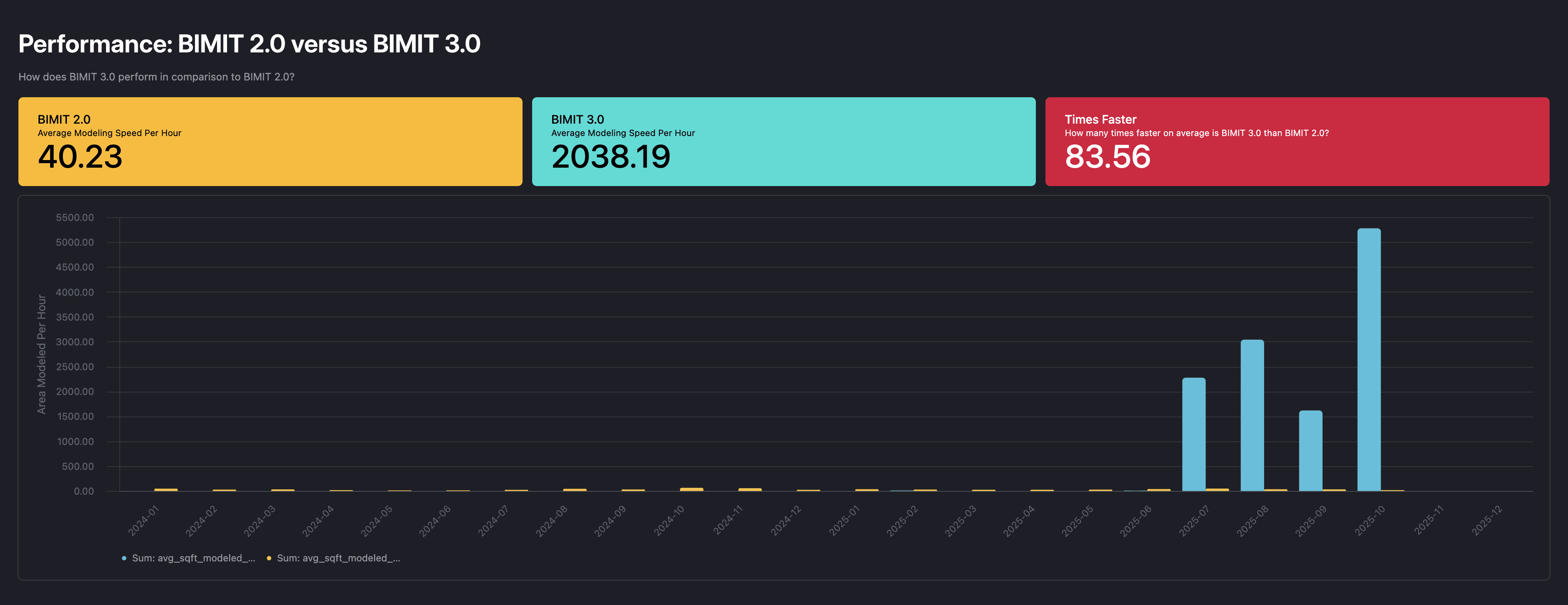

On average, this workflow is over 80 times faster than modeling manually.

Just think about that - what might take a human an hour, we can do in less than a minute.

Square feet modeled per hour is 315 times better on the high end and about 49 times better on the low end

Each of these models expands a dataset that can train machines to "see" the world.

The same way a text-to-image model learns the concept of "apple" by comparing words to pictures, our systems learn what a "wall" or "door" looks like in point-cloud space. The more examples we feed them, the better they generalize. That means the BIMs that we produce today are the sensory data of tomorrow's machines. This data allows its consumers not only to understand what a room is, but how humans use it, maintain it, and adapt it.

The emergence of AI tools like ChatGPT have set off a chain of events, accomplishing what Design Technologists the world over tried (and failed) to do: showcase why BIMs are so powerful and what futures they unlock.

BIMs are crucial to the future of robotics because most neural networks don't yet understand what they're looking at when examining the data they see - they're simply replicating the relationships they've already been exposed to.

Daniel Ince-Cushman puts it well when speaking about the convergence of LLMs & WLMs:

LLMs remain fundamentally limited by their lack of embodiment and environmental feedback. They do not possess a grounded model of the world; their understanding of phenomena such as gravity or thermodynamics is inferential and derived solely from linguistic co-occurrence.

Said differently, neural networks do a decent job telling stories about the physical world but there's another leap required to help them understand how the world actually works.

En masse, BIMs can help machines understand the larger world.

The Next Market

If we collect all of these ideas together, it's clear that this moment holds an enormous opportunity.

Companies are already building machines that move through our physical space

These machines need massive amounts of data about that physical space to better understand and operate within the physical world

Buildings equal data about space and BIMs codify those relationships digitally

To be clear, I'm not simply advocating selling building data to whomever will take it.

I'm stating that properly organized, there's a new market that building data is ready to unlock.

The convergence of consumer-level AI and robotics has promoted the formerly humble BIM from something "you really should do" to one of the most important assets in the built environment. And every single AEC firm has thousands upon thousands of them available.

We are entering a world that needs to account for spaces shared by humans and machines. As within any change, the challenges that will inevitably arise present risk but also an opportunity for those ready to solve these challenges. No one yet knows what kind of market will arise from these dynamics or which new companies will be able to take advantage of the data infrastructure we're all building.

That said, I have a few theories.

In my next post, I'll talk about one of my favorites: that space makers have an extraordinary opportunity to take advantage of the infrastructure we're building to create the companies that will power the next market.

As many, many, many have noted, architecture is in trouble as an industry.

Our business models incentivize the wrong behaviors, the financial rewards for building space are poorly allocated and much of our expertise is often underutilized to make great spaces for those who need it the least. We should be doing what we do best: learning from the world around us and designing better solutions.

Now is the perfect time to leverage the opportunities in front of us to solve the design challenge of making a new kind of business.