Every industry that ends up shaping our daily lives starts the same way:

Fragmented, unreliable, and way overconfident in the wrong places.

Oil was explosive and not very useful.

Iron cracked under the pressures of scale.

Railroads couldn't talk to each other.

Automobiles were expensive toys.

Phones worked, almost never.

And yet, they've become the backbone of modern life. Each fading into the background precisely because they worked. So what changed from their early days? It wasn't novel features or better marketing. I'd suggest it was a shift in focus: someone addressing the bottleneck to scale that everyone else ignored.

Refinement made crude oil usable for everyday life.

Optimizing steel production dethroned "King Iron" as the dominant infrastructure material

Standard gauges turned railroads into nationwide networks.

Parts simplification turned cars from a novelty to something ordinary people could own.

Physical cable networks turned phone calls from a gamble to a given.

Buildings stand at the same inflection point today.

As Integrated Projects works on scaling building digitization from a niche service to a nationwide utility, I can't help but notice the patterns that emerge in history: when variability is removed and trust becomes affordable, scale follows.

Despite decades of software, tooling, and promise of digital twin'ed buildings—building data is still stuck in an early, unreliable phase. Drawings look right until they don't. BIM works until it clashes with reality. The AECO industry lacks trust in the underlying data—a fundamental problem. This unresolved bottleneck has led to a growing disillusionment with the digitization of buildings. Nothing beyond a few select trophy buildings have really realized the benefits of digitization.

By studying lessons in history, the IPX team sees parallels that seem less like coincidences, and more like rules of scale applicable to our mission.

What follows aren’t anecdotes but patterns that unlock scale. Five of them.

LESSON 1

The bottleneck for oil production at scale wasn't extraction. It was refinement.

Crude oil was abundant way before it powered the last 150 years of economic activity.

But in 1859, extracting crude oil from the ground was dangerous (sometimes explosive), inconsistent, and unusable for most applications.

What changed wasn't the drill, it was the refinery; it was in turning crude oil into usable products for everyday application.

The Standard Oil Company treated refinement as an engineering and operational problem rather than an extraction problem solved with expensive rigs. Crude oil became useful to the general public only when it became predictable. That meant: cost control through disciplined procurement, predictable delivery through strategic partnerships and geographical placement of refinery locations, refinement technique advantages through associations with academia and professional groups.

Each activity was a strategic lever that removed variances and made oil predictable.

John D. Rockefeller famously believed that:

“…the secret of success is to do the common thing uncommonly well,”

And refinement became that thing. And that thing, done uncommonly, unlocked breadth.

Standard Oil didn't just sell fuel. Ironically, by perfecting the refinement process it turned refined oil into a platform. Standard Oil produced over 50 oil-derivative products that entered into daily life: kerosene for lighting, gasoline for engines, lubricants for machinery, asphalt for roads, paraffin wax for candles, petroleum jelly, fertilizers, paints, among many other goods. While competitors hoped to strike it rich by finding the next oil well, Standard Oil saw the bottleneck that every crude oil barrel had to pass through: converting it to something useful.

By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled nearly 90% of US refining, proving that oil scaled not by extraction, but by mastering the bottleneck of refinement.

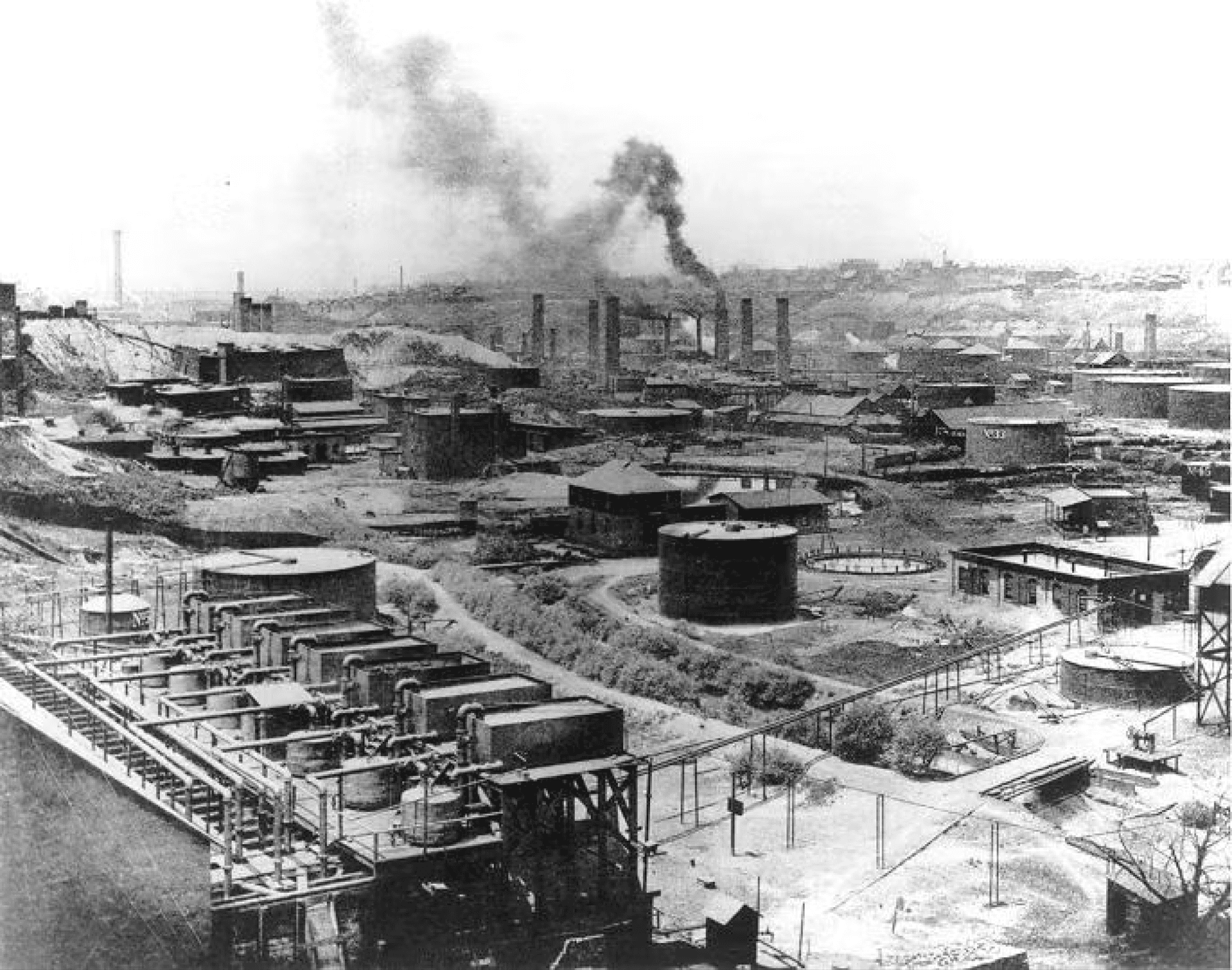

1889, Standard Oil's #1 Oil Refinery in Cleveland, Ohio

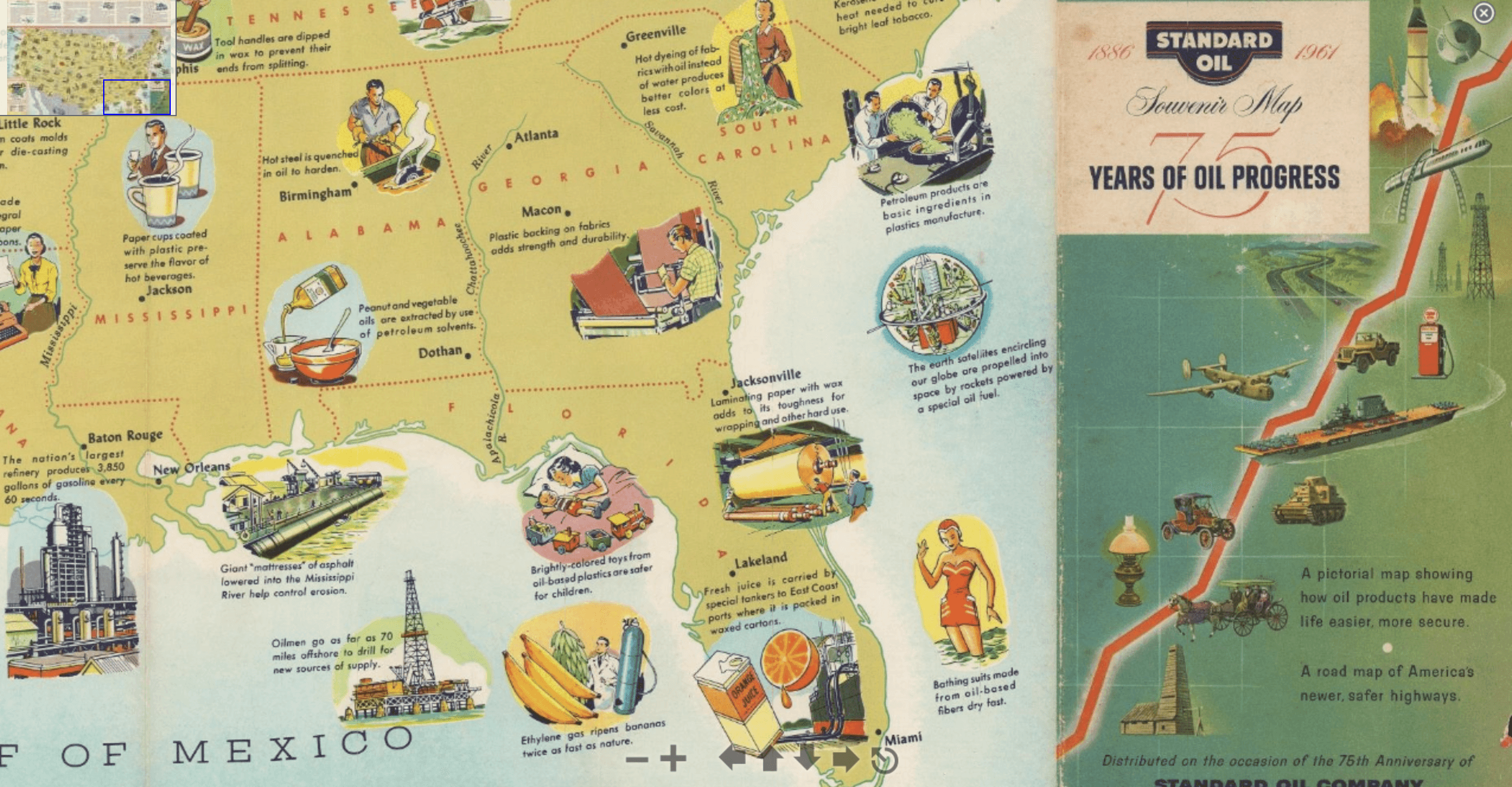

1961 Pictorial Map (snapshot) showing Standard Oil advertisement "how oil-derived products have made life easier, more secure."

LESSON 2

Steel proved that having a structural cost advantage—not just a better product—wins scale.

In 1830, Iron was the dominant material for infrastructure in Britain and the United States. It was dubbed "King Iron."

It was stronger than wood or stone.

But iron was brittle and inconsistent: Bridges collapsed. Railroads warped. Buildings couldn’t rise higher than 6-7 floors. Our ability to innovate our infrastructure was at the mercy of an inferior material. A deeply malevolent king, if one. Iron worked until it was pressured to scale, consistently.

And then came steel.

Carnegie Steel Company didn’t invent steel, but industrialized its production.

The breakthrough was in adopting the Bessemer process, developed by Henry Bessemer in the 1850s. Before the Bessemer process, steel was slow, expensive, and inconsistent to make. Production took days or weeks. Quality varied batch to batch. Steel was effectively a luxury material undifferentiated from iron.

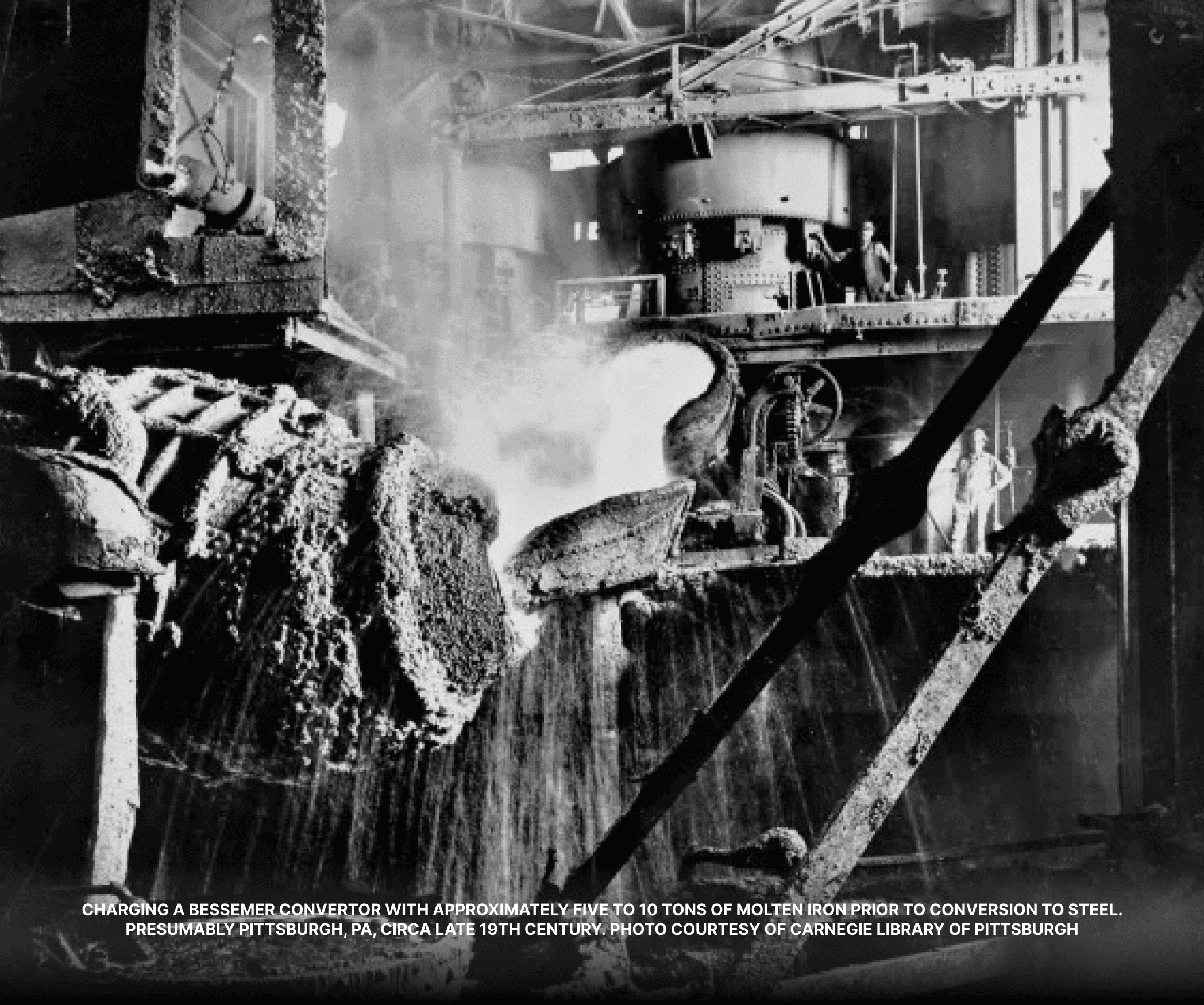

Carnegie Steel Company implemented the new process doing one simple but radical thing: it blew air through molten iron to remove impurities quickly. That operational change (and later open-hearth steelmaking) cut production time from weeks to minutes, making steel predictable, not artisanal.

Per-ton steel prices fell from $160/ton in the 1860s to under $20/ton by the 1890s—an unbeatable cost advantage that enabled Carnegie Steel Company to undercut competition, capture massive market share, while maintaining margin. While competitors still treated steel as a premium material, the Carnegie Steel Company delivered it even cheaper than iron.ˣ Steel stopped being a craft. It became a trusted, consistent process. Trust earned attention. Producing the trusted material cheaper than their competitors led to scale through consolidation.

Qualities | Wrought / Cast Iron | Steel |

|---|---|---|

Dominant Era | Pre-1870s | 1870s onward |

Production Method | Small batches, labor-intensive | Industrial, process-driven |

Production Time | Days to weeks per batch | Minutes to hours |

Cost Curve | High & slow to decline | Rapidly declining with scale |

Material Consistency | High variable quality | Standardized, predictable quality |

Strength | Strong in compression, weak in tension | Strong in both compression & tension |

Flexibility | Brittle, prone to cracking | Ductile, resilient under stress |

Durability | Shorter lifespan under heavy use | Longer lifespan, less fatigue |

Scalability | Constrained by craftsmanship | Enabled mass infrastructure |

Economic Impact | Supported early industrialization | Enabled cities, rail networks, global trade |

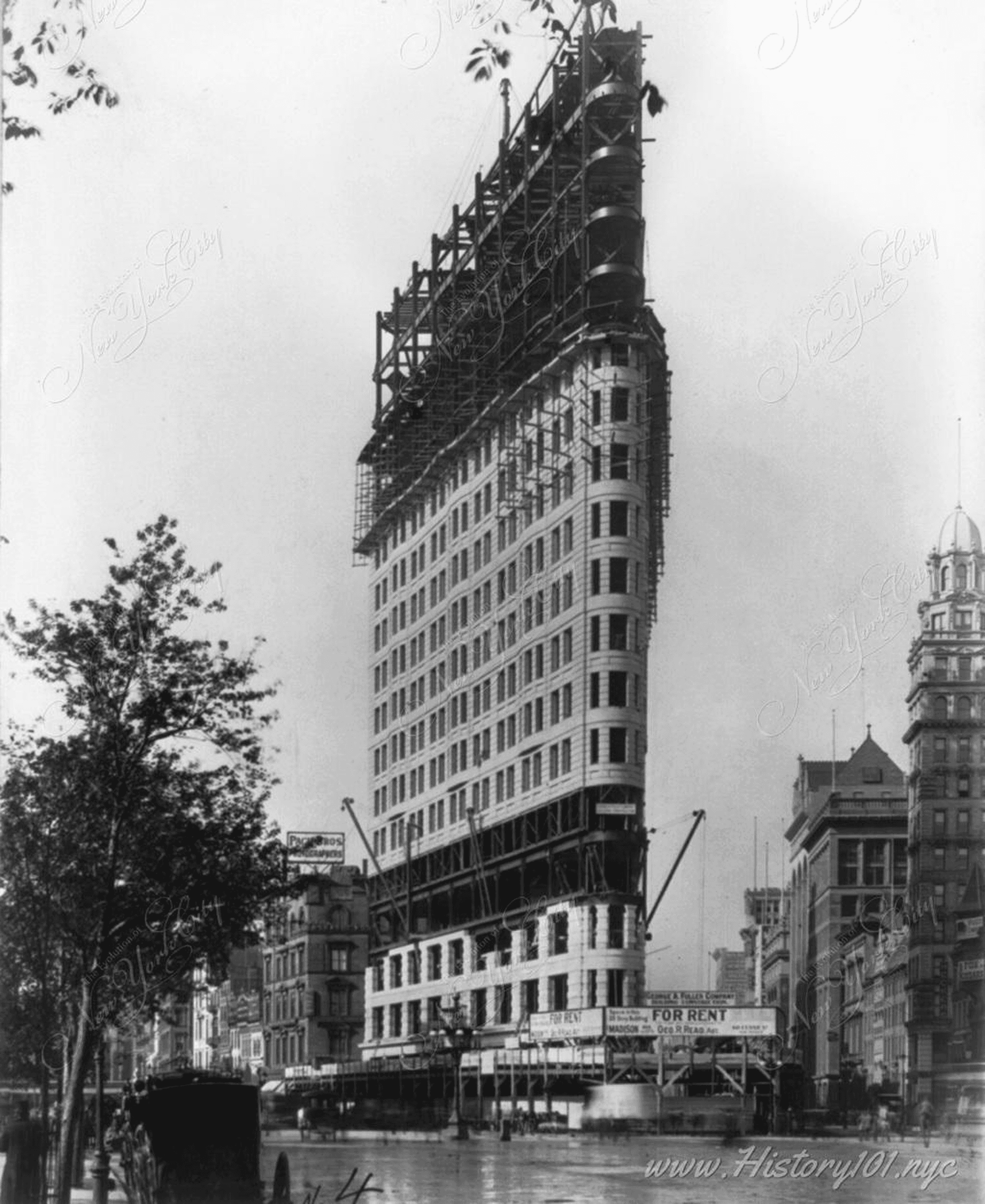

1902, Flatiron Building Construction. Reliable steel enabled faster and taller building structures across America.

LESSON 3

To scale nationally, railroads didn’t need faster trains. They needed standards.

Before 1850, American railroads were not a system. They were a collection of local businesses.

Each railroad company had to set its own schedules, operate in specific regions, and chose its own track gauge (the distance between rails). Track gauges ranged wildly: 4 ft-8.5 inches, 5 ft, 6 ft, etc.ˣ This meant a train could not continue onto another company's tracks. So when freight reached the end of a line, cargo had to be unloaded and manually transferred to another train.

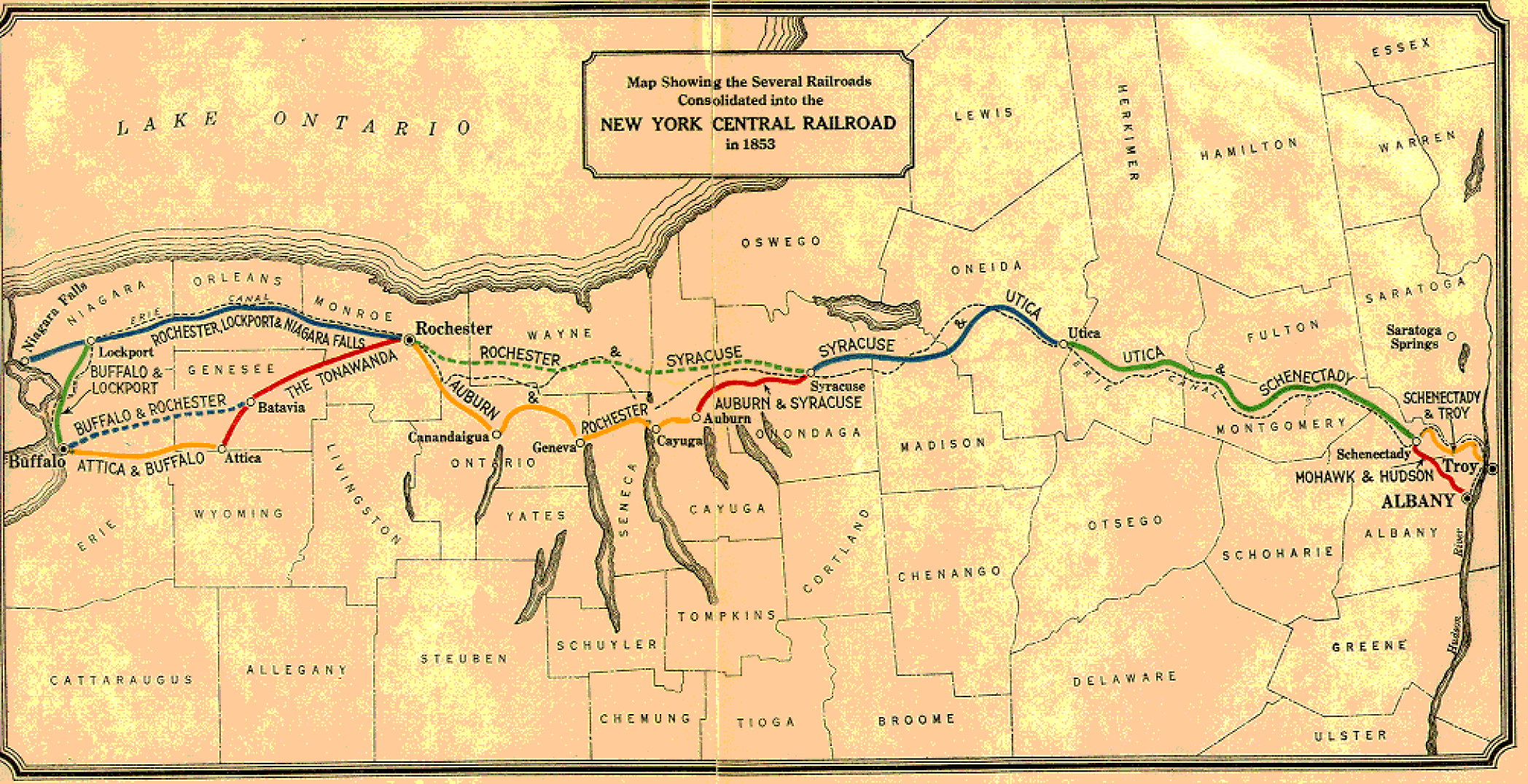

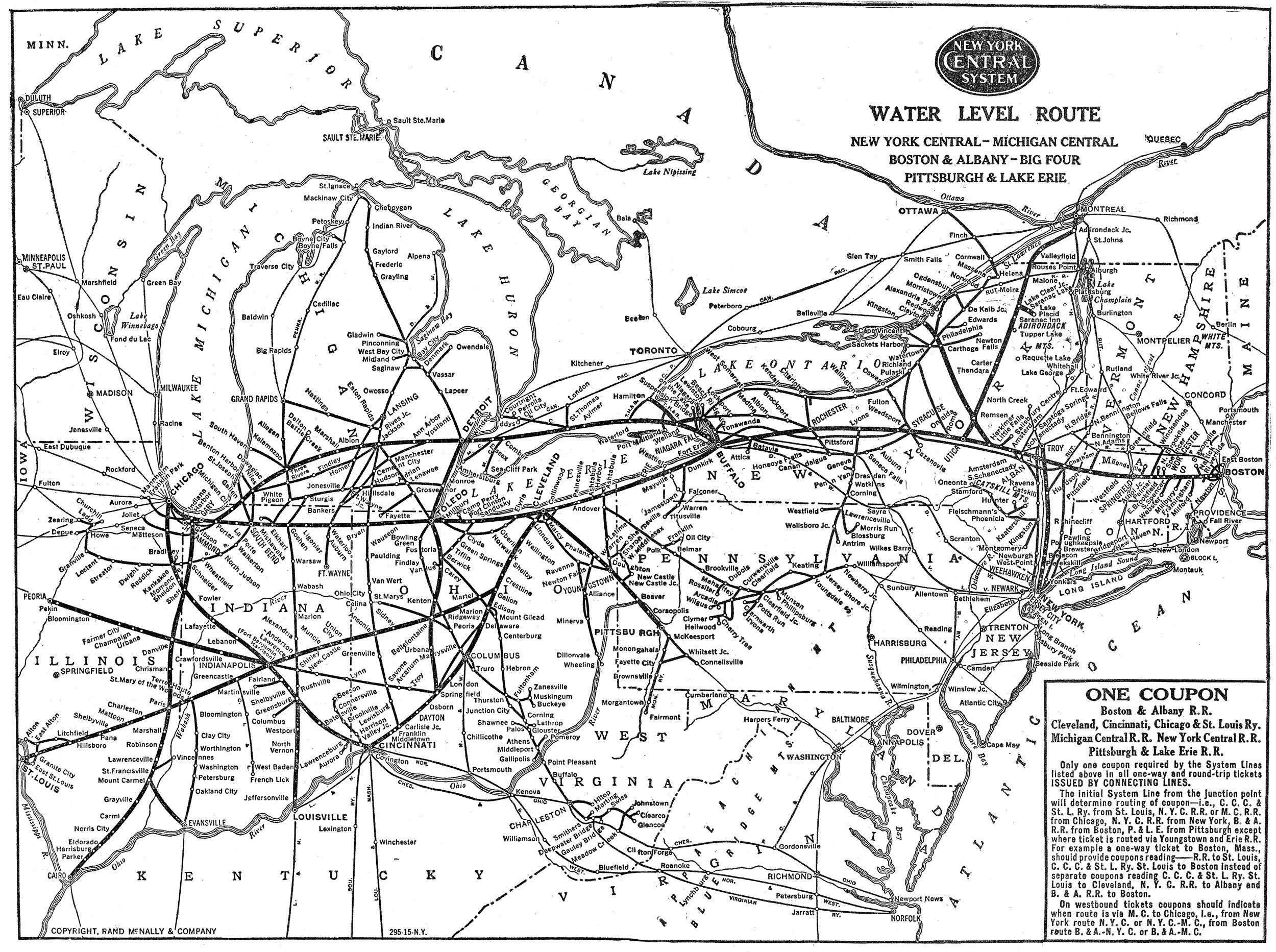

The New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, led by Cornelius Vanderbilt, understood: local optimization was the enemy of national scale. Vanderbilt did not invent standard gauge railroads, nor did his company single-handedly decree a national standard.

What Vanderbilt did was more subtle—and operationally effective. The real contribution was operational standardization at scale.

Consolidate multiple regional railroads

Convert acquired lines to compatible gauges

Standardize timekeeping, scheduling, and routing

Focus on throughput and reliability, not novel systems

Standardization was brutal. It required New York Central to physically move rails, re-space ties, rebuild switches and depots, temporarily shut down lines, and went as far as standardizing time itself, collapsing hundreds of local clocks into four time zones to keep nationwide schedules coherent (well before a federal mandate). It was expensive, controversial, and unpopular—initially.

But by the 1870s, New York Central was the first to move freight from Chicago to New York without a single unload. Something no local railroad business could match. Uninterrupted service reduced delays and costs by nearly 70% by the end of the century, which resulted in New York Central absorbing a disproportionate share of east–west freight traffic.ˣ

By 1880s, no one marveled at the rails anymore. They relied on them. The railways evolved from a novelty to infrastructure by standardizing the rails.

1853 map showing several, isolated rail lines consolidated into the New York Central Railroad. Credit to Legacy.

An official, 1940 system map of the New York Central Railroad. Credit to American Rails

LESSON 4

The "car for the great multitude," started by stripping down its parts

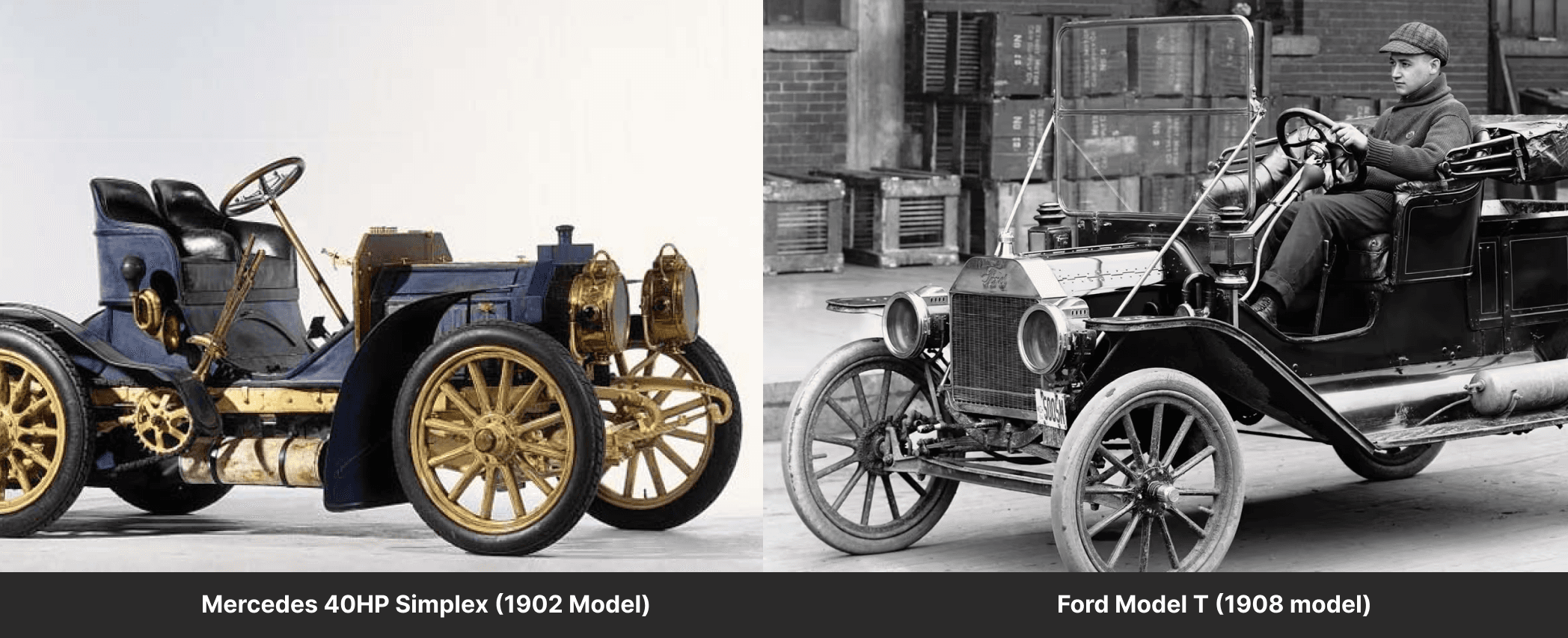

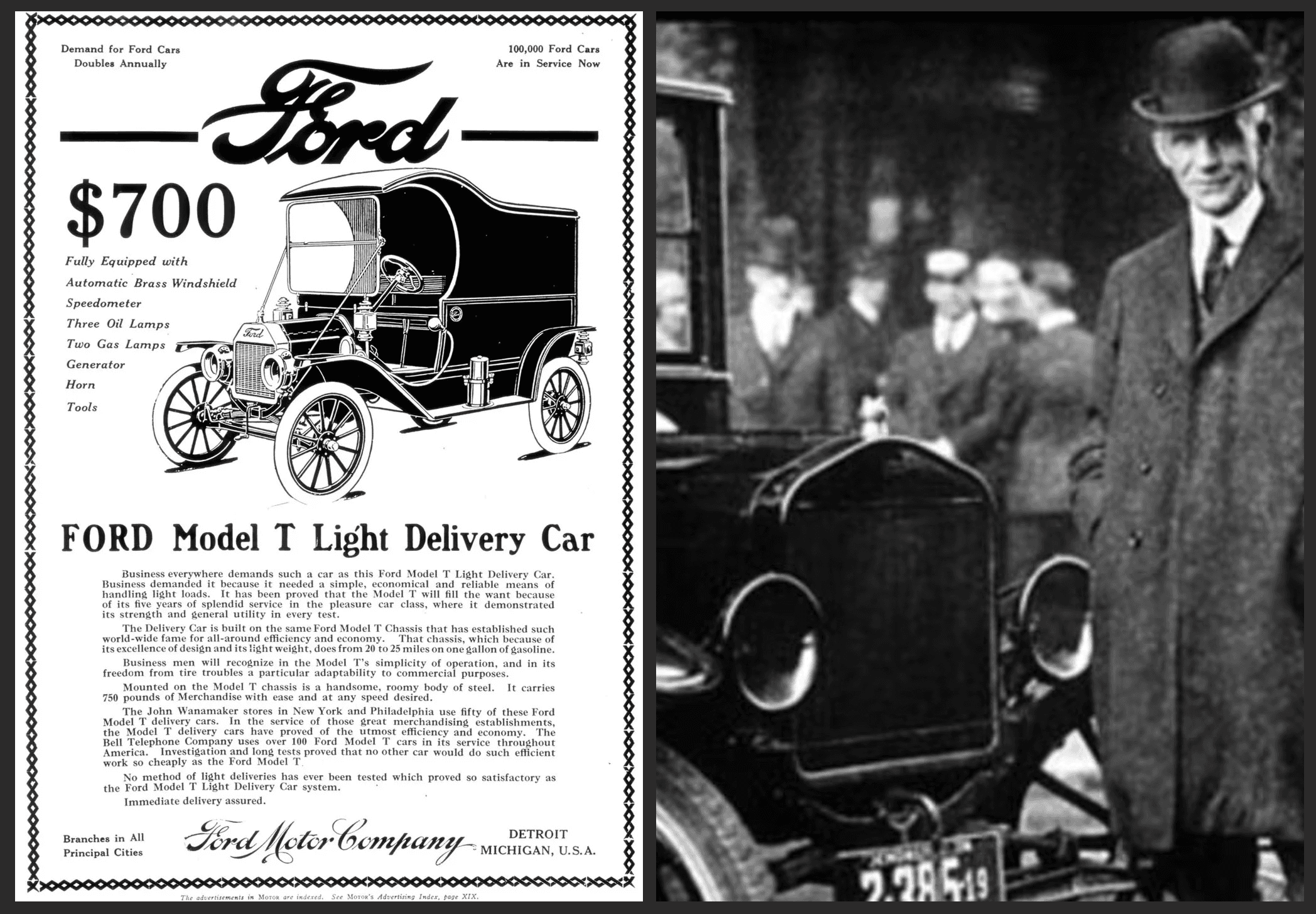

At the end of the 1800's, the automobile wasn't a symbol of progress. It was a public nuisance.

There were more than 500 automakers in the United States, most producing hand-built, elaborate machines that cost $3,000, more than 5x the average annual household income of $600.ˣ Roads were dirt.ˣ Horses could navigate where cars failed. So they broke constantly. Car mechanics were rare and expensive. Newspapers and politicians openly mocked the automobile as a toy for the wealthy. In 1906, Woodrow Wilson called the car “a picture of the arrogance of wealth.” Anti-car activists tore up roads and sabotaged parked vehicles.

This context matters because when The Ford Motor Company entered the market in 1903, they didn’t compete by making a faster car or a prettier one. They won by redesigning the production system: stripped the car down to the fewest parts possible. A process that could be repeated thousands of times, anchored by a obsession to simplify. Ford famously is attributed by stating in his autobiography:

"Whenever anyone suggests to me that I might increase weight or add a part to my car, I look into decreasing weight and eliminating a part."

Ford’s obsession with simplicity wasn't aesthetic. It was the company's modus operandi. The Model T was built on a single standardized chassis, fully interchangeable parts, and famously had almost no variants in the early days. Assembly time fell from roughly twelve hours in 1912 to just 90 minutes by 1914—with one car coming off the line every 24 seconds.ˣ As repetition replaced craftsmanship, costs collapsed by expanding the labor pool to unskilled workers to join the car manufacturing process. The price of a Model T dropped from $825 at launch to under $300 within two decades.ˣ

By 1924, The Ford Company's Model T accounted for nearly 40% of new cars on American roads.ˣ

Qualities | Ford Model T | Typical Car in 1900 |

|---|---|---|

Target market | Mass market | Wealthy elites |

Price | $825 (1908); $260 (1925) | $1,500 - $3,000 |

Relative Cost | 1-1.5x annual income | 4-6x annual income |

Annual Production Volume | Millions | Dozens to hundreds per model |

Assembly Method | Moving assembly line | Hand-built, artisanal |

Assembly Time | From 12 hours down to 90 minutes; one car off the line every 24 seconds | Weeks |

Parts Interchangeability | Fully interchangeable | Limited or none |

Variants | Extremely limited | Highly customized |

Repairability | Simple, field repairable | Specialist repair required |

Assembly Skill Required | Semi- to low-skilled labor | Skilled craftsmen |

Tolerance for Poor Roads | High; due to light weight | Low; due to heaviness |

LESSON 5

Communication didn't scale with the telephone. It scaled with physical cables.

Before smartphones, you were lucky if a phone call connected at all.

Early telecom companies didn’t try to win by shipping better phones or by adding features faster than competitors. They focused instead on something far less visible: making connection universal, predictable, and boring.

From the 1890s through the 1910s, the phone itself already worked. The cabling system did not.

Networks were fragmented, incompatible, and unreliable. Voltages varied. Protocols differed. Long-distance calls were expensive and uncertain, often routed through multiple human operators and prone to failure. Owning a phone didn’t mean it would work—especially outside major cities. This was not unlike the challenges the rail industry faced with varying rail gauges, and private networks not working together.

The breakthrough came when AT&T treated communication as an infrastructure problem, not a product problem.

Their advantage was operational discipline:

Standardizing cables,

Switching systems & voltages, and

Operating rules across geographies,

Building redundancy.

Investing heavily in physical infrastructure users would never see. The goal was not to sell features or products, but to make communication so dependable that no one thought about it at all. AT&T’s tagline crystallized its modus operandi: “one system, one policy, universal service.” Once cables were laid, networks were stabilized, then culture followed: businesses reorganized around real-time communication. Markets synchronized. Distance shrank.

AT&T’s push toward universal service accelerated in the 1910s, with major milestones:

1915: First transcontinental phone call (New York to San Francisco)

1910s–1920s: Rapid standardization of line switching and long-distance lines

1920s-1940s: call reliability improved enough that business depended on it

1950 - 1970s: Underwater lines laid to establish international connections.

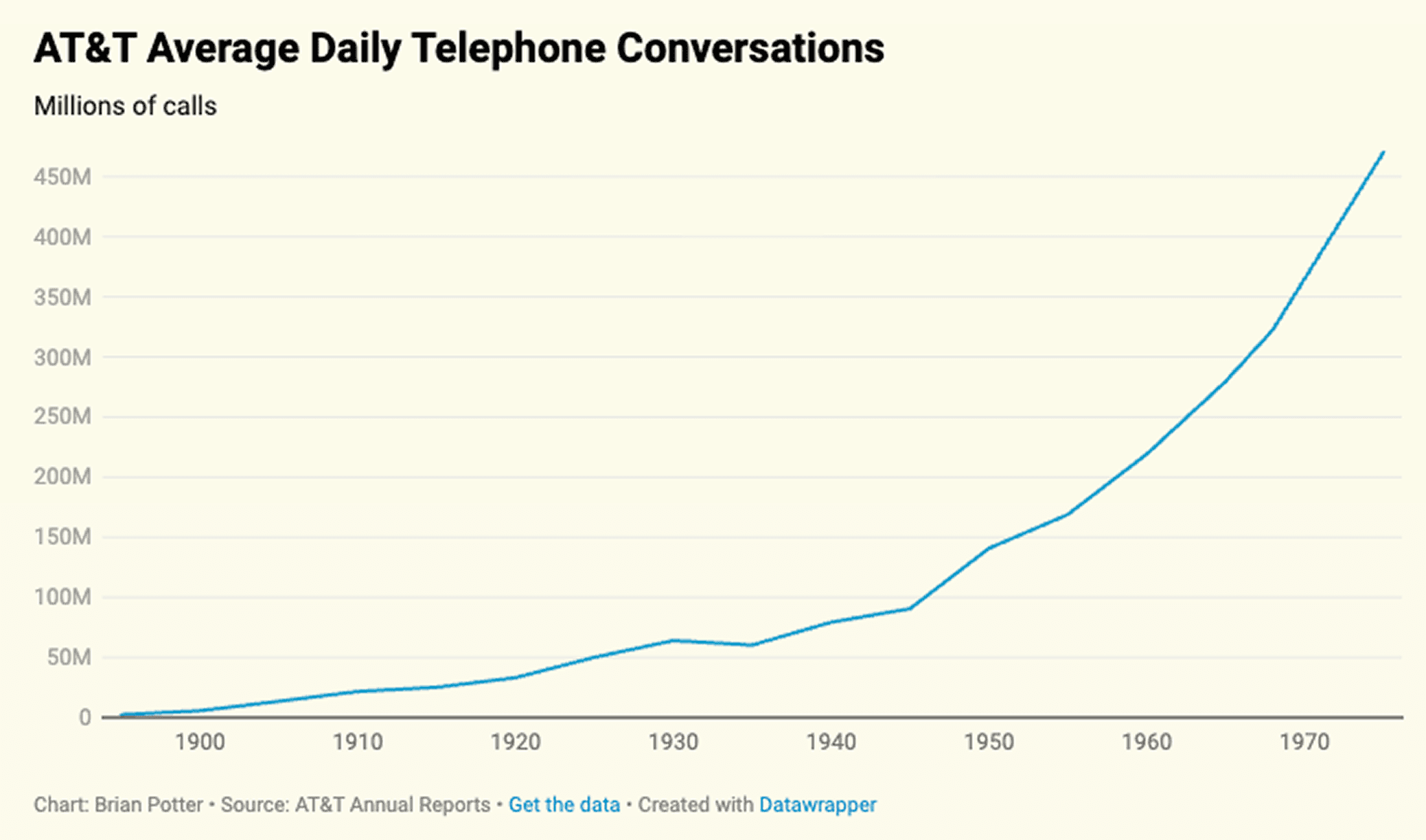

Only after coaxial physical networks were in place did downstream industries emerge. Brian Potter of Construction Physics made a similar case highlighted in this chart.

BUILDINGS ARE NEXT

Seen together, these stories reveal the same foundations of scale required to digitize millions of buildings, not just a select few:

Rockefeller: Master the refinement process by turning crude oil (raw scan data) into usable, everyday formats (BIM —> CAD).

Carnegie: Achieve cost advantage by adopting frontier tech and best practices (go from one-off rates to predictable, consistent pricing).

Vanderbilt: Set the standard, schedule, experience—and focus on reliability.

Ford: Scale through subtraction, not addition. (Focus on eliminating elements, not adding to a growing catalog of options).

Bell System: Create global connections by laying the cables for reliable distribution.

Building digitization is still early in this arc. Building information is outdated and fragmented across:

Reality capture hardware (the oil drills),

Authoring & coordination software (phones & features),

Localized scan-to-BIM services (independent businesses),

Definition & standards

The fact that the AECO industry still debating design authoring tools, LOD definitions, faster scripts to perform outdated workflows is a sign that the foundation isn’t finished yet. The opportunity is to do what every enduring industry did before:

…find the bottleneck, sit inside it longer than anyone else is willing to, and make it reliable at scale.

When building data becomes legible, available and reliable—when accurate, standardized building plans are as normal long-distance call or trains arriving on time—the change will feel sudden.

Integrated Projects exists to address the same bottleneck every enduring industry faced: uncontrolled variability at the foundation. By treating scan-to-BIM as production infrastructure—standardized, repeatable, and automatable—IPX is building the conditions for building data to become reliable at scale for every owner-operator, designer, and builder.

KEY TAKEAWAY

History is remarkably consistent about how scale is unlocked.

First, a company accepts the unglamorous work of disciplined operations to address a bottleneck to scale—which usually means limiting variability.

Simplification removes variability.

Less variability means fewer parts.

Fewer parts enables cost control, repetition, and quality.

Quality builds trust.

Trust breeds scale. And also, better negotiation power.

Negotiation power means even better costs.

Better costs means more consumer adoption—and more scale.

Only after that do new behaviors emerge—new markets, new industries, new ways of working.

Infrastructure doesn’t announce itself when it’s built. It announces itself when no one has to think about it anymore.

But like oil, steel, railroads, cars, and cable before them, it will have been earned quietly. That is the work IPX is doing now: addressing the bottleneck by simplifying scopes, improving quality of digital building models, forcing repetition which lead to better digitization costs, one building at a time, until buildings stop being rediscovered and start being understood. All 1.6 billion of them.

Gradually, then suddenly.

——————————————————-

Jose Cruz Jr. is the Founder and CEO of Integrated Projects.

Integrated Projects (IPX) is a spatial intelligence company focused on turning physical buildings into accurate, standardized digital information models, enabling organizations to acquire, design, renovate, and operate buildings with confidence.